Contents

Introduction

If you feel you’d like a greater understanding of clients and customers, then you’ve come to the right place. If you really want to learn what makes people tick, influence decisions, and the pathways customers’ take, then read on.

Welcome to the world of Behavioural Economics.

In this white paper, you will learn the theories that sit behind Behavioural Economics and the heuristics we all employ when assessing situations, forming preferences and making decisions. Then, we explore how firms can use this knowledge of Behavioural Economics techniques ethically, both internally and at every consumer touch point. The aim is to show firms how a knowledge and awareness of Behavioural Economics, when deployed ethically for the benefit of consumers, can both assuage regulatory concerns and drive improved commercial outcomes by ensuring clients and consumers are always provided with the most appropriate product or service.

Don’t have time to read the whole white paper right now?

No worries. Let us send you a copy so you can read it when it’s convenient for you. Just let me know where to send it (just takes 5 seconds).

The series will explore a variety of Behavioural Economics phenomena that commonly influence decisions in financial services.

- Section one looks at the heuristics that drive our judgements and how we assess a situation.

- Section two will look at how emotions and the way a choice is framed can affect people’s opinions and beliefs.

- Section three will examine the tendency to pigeonhole decisions, how we compartmentalise our lives and avoid examining the bigger picture. This dismissal or selectivity with wider contexts is known as Mental Accounting.

After exploring how these phenomena affect the financial services industry, the final two white papers will explore the ultimate question all such theories have to answer… ‘so what?’.

- Section four will suggest measures firms can take, at an organisation or division wide level, in response to Behavioural Economics phenomenon.

- Section five will explore how individuals can adjust their sales, pitching and general communication style given the effects of Behavioural Economics.

1) Understanding Perspectives

People – Understandable but not Rational

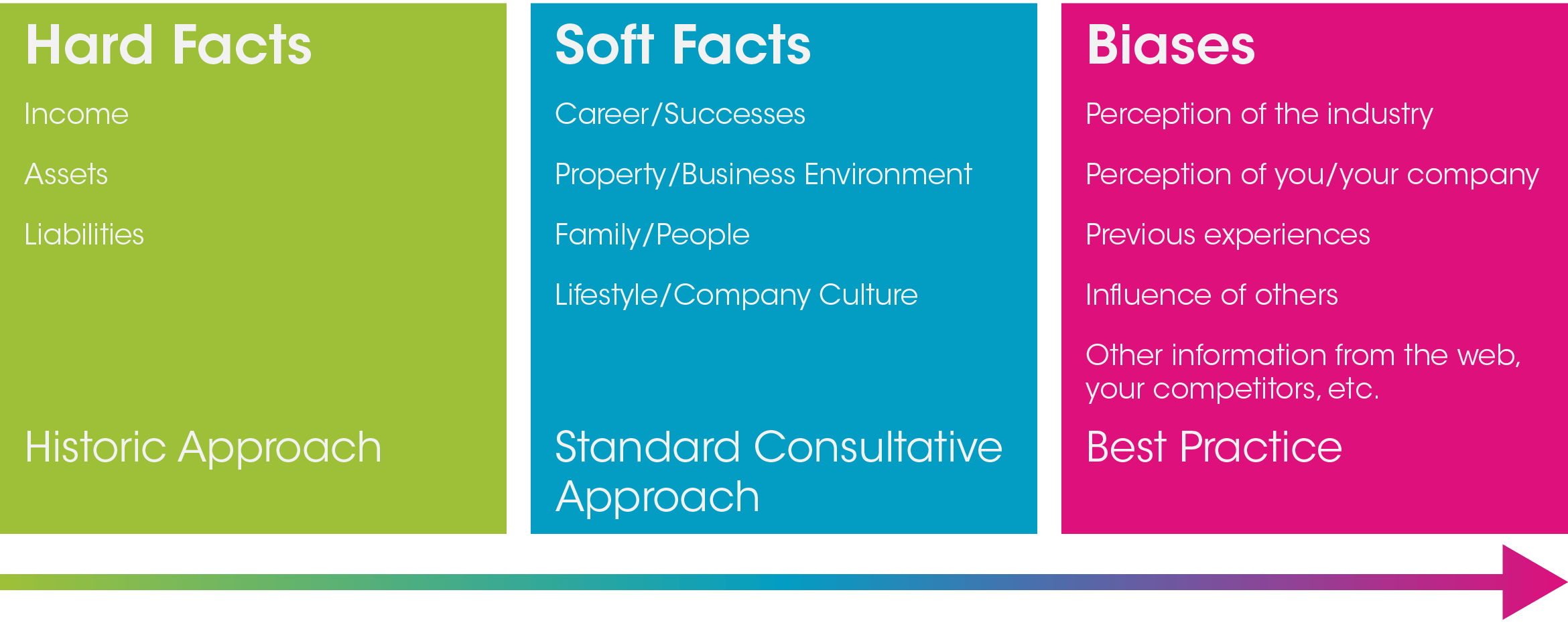

Traditionally, professionals in the financial services industry and beyond have worked from the principle that people make judgements in accordance with Von Neumann and Morgenstern’s Expected Utility Theory and Savage’s Subjective Expected Utility Theory. In these theories it is presumed that people will act in an unbiased fashion to maximise their own self-interest. The theories presume that people apply probability rationally to consider all relevant data, with unlimited cognitive ability and no time constraints, to lead to the most logical and beneficial outcome.

We can all see the flaws in this thesis, though most people would accept there are rules and logic to their decision making process. Leading Behavioural Economics theorists, including Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky and Richard Thaler, have tested these psychological rules to identify those heuristics or ‘rules of thumb’ most commonly deployed in decision making. Their findings proved that traditional economic theory is fatally flawed in that it does not accurately consider the effect human participants have on the business world.

When considering the judgement heuristics outlined below it is important to remember:

- Heuristics affect us all – Behavioural Economics theorists have found that we all apply heuristics. Our brain relies on them to assess situations and make decisions quickly and efficiently. An understanding of heuristics will not stop you from automatically applying them and even succumbing to their pitfalls. The theorists have many anecdotal examples of how even those with a detailed knowledge of psychology and statistics can be affected by the most common heuristics when they think intuitively. It is important to remember that heuristics are not just affecting your clients; they are also affecting you and your colleagues.

- People won’t apply every heuristic every time – Behavioural Economics cannot simply replace economic theory with a new model for understanding economic drivers and trends. It is impossible to write a new ‘rulebook’ as we do not apply heuristics consistently. Some heuristics even appear to contradict each other. It is important to remember that one client will not approach a situation from the same standing point as another. Even if clients appear to be similar they may apply different heuristics and thus may come to very different conclusions, even if logic would suggest that the same outcome would actually be the most beneficial for them both. Conversely, just because people all apply the same heuristic and reach the same conclusion does not mean that it is the best way forward.

- Awareness of Behavioural Economics can be used for good and ill – An awareness of Behavioural Economics will not automatically result in beneficial outcomes for your clients. An understanding of the heuristics used in judgements and decision making purely provides you with the tools to fully appreciate and influence the client’s decision making process. It is up to you to utilise that knowledge and deploy techniques that will influence their decision in the right way. This will be explored further later but throughout the series we will identify examples of ethical and unethical deployment of Behavioural Economics. Remember…as our comic books remind us …. “With great power comes great responsibility”.

Judgemental Heuristics

Usually, people reduce the complex task of forming expectations and assessing probabilities to simpler judgemental operations. While this can speed things up and enable people to make a thoughtful decision without undergoing complex mathematical assessments and evaluations, it can lead to systematic errors known as biases or cognitive illusions.

Judgemental heuristics arise when people evaluate an event using similarity. They allocate greater levels of importance or value to a particular event, situation or choice because they are linking it in some way to another data point or group. If it was possible to see the event as a completely unique entity, they would evaluate it differently. This can lead to the following;

Overreaction to New Information or Base Rate Neglect – People give too much weight to new information, neglecting the original data (the base rates) they were originally provided with. The more personal the new information is, the more likely they are to reject the overarching base rate. For example:

Tversky and Kahneman ran an experiment where subjects were shown descriptions of 100 professionals. Before reading the descriptions, they were told that 70 were engineers and 30 were lawyers. (This is the base rate data). They were asked to choose which profession they thought was more likely for each description. When faced with a description that was intended to be neutral, instead of applying the base rate data and concluding that there was a 70% chance it was an engineer, subjects purely used the new information and saw a 50% chance either way.

Such overreactions can be common when clients are attempting to judge financial choices. In 2010 it was shown that only 24% of actively managed funds managed to beat the benchmark stock market (the FTSE All Share). Thus the majority of clients paid for active management when they would have seen a better return from a cheaper passive fund. Even if a client is made aware that the evidence is stacked in favour of passive management, they can still be wooed by a fund manager with recent strong performance. They can give far more weight to the fund manager’s own results than to the low base rate of 24% success.

Underreacting to New Information or Conservatism – People can also undervalue new information, underreacting to new data which should fundamentally shift their prior beliefs. Many financial service professionals may have felt the effects of this heuristics when studying the new regulations in our industry; they may have been tempted to dismiss this new information that suggested what they had previously considered best practice needed adapting.

The Conservatism heuristic may partly explain why, in 2008, BBC Watchdog found that despite consistent evidence of poor service from Banking Current Accounts, married couples in Britain were more likely to get divorced than change their Bank Account. The response, in turn, to this information was small with little change in consumer behaviour and a 5 year delay until new regulations were brought in to make switching easier in 2013.

Misunderstanding Chance: Conjunction Fallacy – People can misunderstand the effect of considering several possibilities at once. Intuition can suggest that a combined probability is more likely than one single event, when mathematically this cannot be the case. For example Tversky and Kahneman presented subjects with the following description:

“Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with the issue of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.”

Subjects were asked whether it was more probable that Linda was A) A bank teller or B) A Bank teller and active in the feminist movement. The majority of the subjects thought B) was more likely than A), even though B) has two conditions, so is statistically less probable.

Thus, people can make assumptions based on stereotypes and a misunderstanding of chance. In financial services, the conjunction fallacy could lead to confusion around the respective benefits and weaknesses of particular options.

The conjunction fallacy may also affect how clients judge financial institutions. Clients may think that the likelihood a Bank has an excellent mortgages service and a great credit card offering is greater than them outperforming their competitors in just one of these fields. Statistically, though, it is more likely that an institution would excel in one field than in two. Thus the conjunction fallacy may contribute to a consumer’s decision to take out a credit card from their mortgage provider without any significant research. The conjunction fallacy has the potential to either undermine your sales strategy or help you cross sell more products.

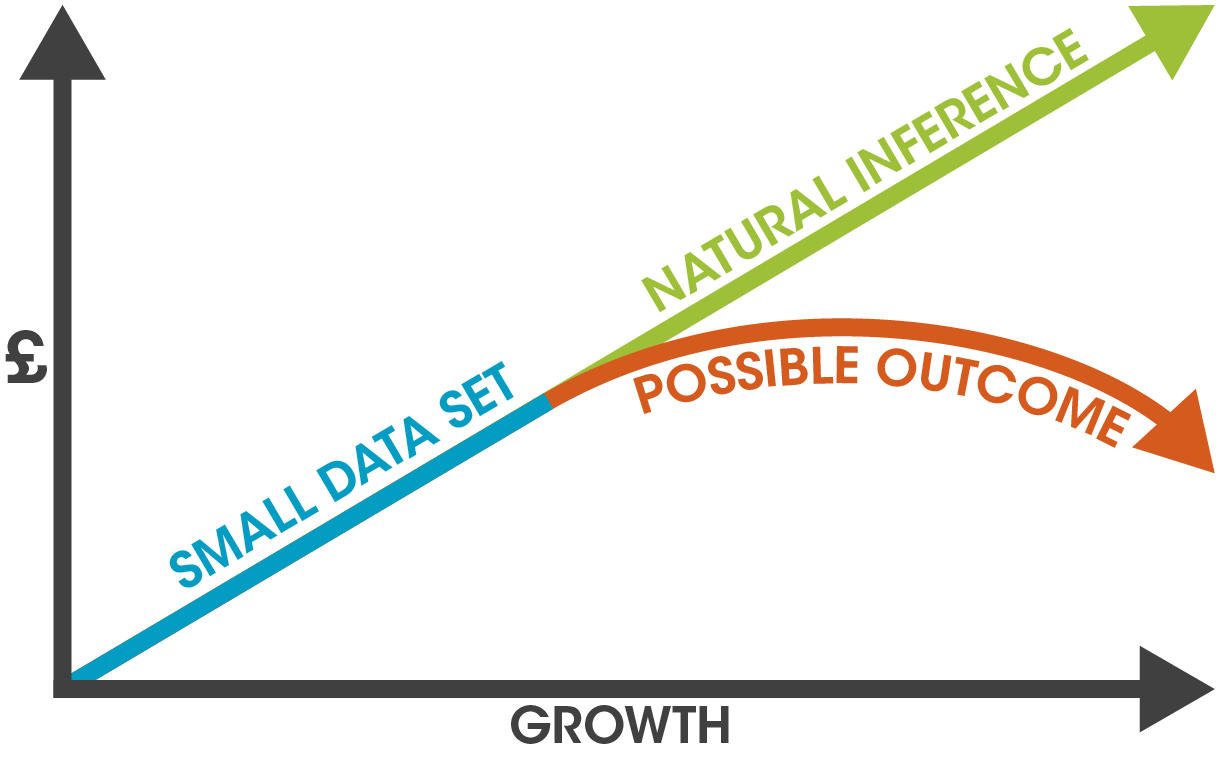

Misunderstanding Chance: Law of Small Numbers – When people don’t have access to a full set of data they often attempt to infer it from the few data points available. They presume that the trends in the data provided are common throughout the full data set. For example, people may believe a stock market analyst is good after just four successful predictions in a row. Or, looking at a graph, they may extrapolate that the graph will continue on the same gradient for decades even though the graph only pertains to results from the last 12 month. Advisers should be particularly aware of this phenomenon when selling long term products like pensions. This effect can be used unethically to sell poorly performing products and harnessed ethically to help portray the best product in the best light. We recommend advisers always explain to clients and consumers the extent of the data they have used, how it might be realistically extrapolated and the pitfalls of extrapolating the data too far.

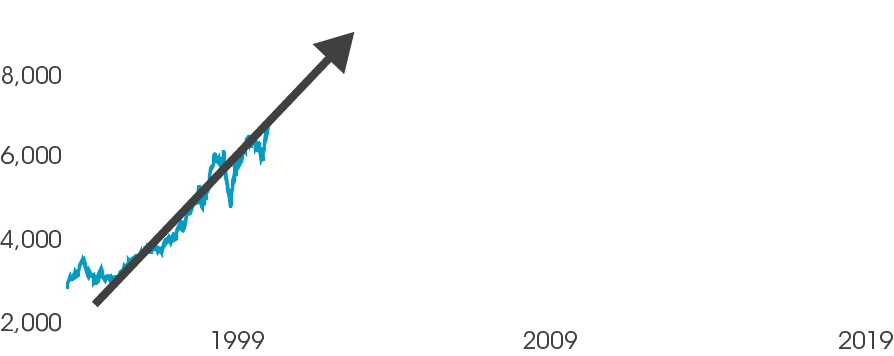

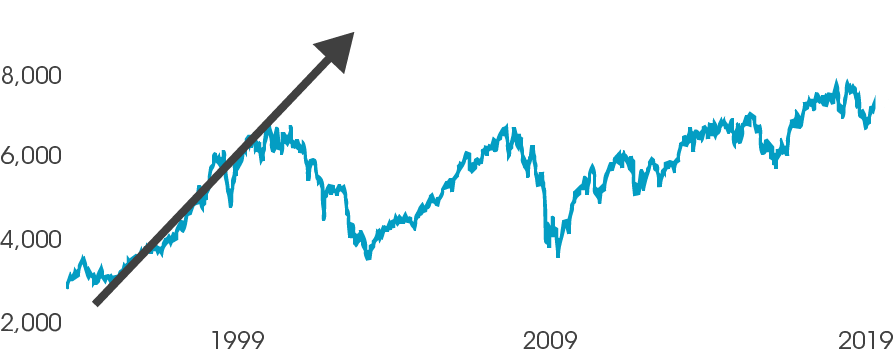

When we consider this effect in the light of the FTSE 100, it is easy to see how this heuristic can have a large impact on our industry. If we consider the FTSE 100 over the past 20 years, it is clear that the index has experienced several significant dips in that time. Agents viewing the data at the moment before the dip could easily have been extrapolating a much stronger future for the fund.

People presented with the graph above may naturally extrapolate the data as indicated by the purple line. However, this can now be considered a small data set. The ‘Law of Small Numbers’ means we naturally believe that the data in Figure 2 is common of the whole data set. However, if we look at the FTSE over the last 20 years, we can see this gradient was exceptional in that it was preceded by a relatively soft gradient and followed by a large dip. The heights indicated by the extrapolation have still not been reached, almost 19 years later.

Misunderstanding Chance: Gamblers’ Fallacy – Linked to the ‘Law of small numbers’, The Gambler’s fallacy is the belief that chance is a self-correcting process. It is the natural belief that after tossing a coin four times and seeing four heads, tails is now ‘due’. This is not the case, as even with a coin toss the 50/50 chance can only been seen over a much larger data set.

This can be a common and risky phenomenon in any sales force. After losing several pitches through ‘ill luck’, a team can begin to think they are ‘due’ a win. While such a mentality can help bolster morale, it can also delay an investigation over what might be done to improve. A belief that chance will ‘correct’ itself in one’s favour can lead to people continuing down a path despite a great deal of evidence that suggests the current trend is in the other direction.

Overconfidence – People are generally overconfident in their abilities. Tests have shown that when people describe themselves as “99% sure”, they are generally right only 80% of the time. However, when they rate their performance after an event their overall accuracy improves greatly. Prior to an event, people are prone to a number of biases that result in a short term exaggeration in self-belief.

Cooper, Woo & Dunkleberg interviewed new entrepreneurs about their chance of success while asking them about ‘base rate’ examples for enterprises similar to their own. Their self-assessed chances did not correlate with objective factors like higher education, prior supervisory experience or initial capital. Over 80% of entrepreneurs perceived their chance of success as 70% or better, with one-third describing their success as certain. However, on average they said the chance for success of business like theirs was only 59%. Even this is optimistic; the average survival rate for new firms after 5 years is around 33%.

Overconfidence can result in a number of biases, including;

- A exaggerated confidence in one’s own ability to predict the future

- The tendency to overestimate the value of one’s own knowledge

- A belief that one’s abilities are better than those of others

- Excessive optimism or wishful thinking

- A belief that one can control completely random events – known as an illusion of control

- A tendency to view success as a result of one’s own abilities and failure as a result of bad luck – known as self-attribution bias

- A belief that one predicted this future beforehand when in fact it was only identified after the event – known as hindsight bias

These biases can result in a warped assessment of a situation where the individual is directly involved. While the Mortgage Market Review (MMR) legislation has now provided some protection for consumers, it is the adviser’s responsibility to be aware that consumers may be reluctant to accept the industry’s assessment of their financial situation. While regulation now prevents lenders lending to those who are unlikely to be able to meet their repayments, the overconfidence heuristic may result in clients believing they should be an exception to lending rules.

It is also common for financial professionals to fall foul of the overconfidence heuristic, as they begin to believe they have greater powers than their colleagues to assess the current financial trends. It is arguable that the overconfidence heuristic was a significant driver of the recent financial crisis. Indeed, it can be found when nearly all financial bubbles burst.

When overconfidence is combined with misunderstandings of chance, financial professionals can begin to overestimate their chance of success, underestimating the importance of any elements outside of their personal control.

March and Shapira found that Fund Managers tended to view risk as something to be overcome via skill and good choices. While managers accepted the possibility of failure, they saw themselves not as gamblers but as prudent agents in control of people and events.

Overconfidence can also affect an organisation as a whole. In business, optimistic forecasting can mean that projects are given higher expectations. When projects then fail to meet these unrealistic expectations, outcomes can be viewed as a loss even though in reality they are an improvement on previous efforts. Organisations are as prone to the optimism heuristics as individuals. Most companies value optimism, shun those who are too pessimistic and deliberately set high goals to motivate employees. A clear example of this is firms’ attitudes to capital investment projects. Often projects can finish late, come in over budget and fail to achieve their initial objectives. However, firms are prone to be grossly optimistic about an investment if it involves new technology or otherwise places the firm in unfamiliar territory. This can be seen as a corporate overconfidence.

Ambiguity Aversion – Arguably the opposite of overconfidence, when people feel they do not have enough information and that the choice before them is ambiguous they attempt to avoid it altogether. In some ways, this can be seen as a safety net to stop us taking wrong decisions. However, it can result in inefficiency and stagnation. The ambiguity aversion is common in the financial services industry, with consumers often failing to take out life cover or a pension because the decision is simply too difficult. This affect may increase as some argue many consumers are becoming priced out of the advice market as a result of RDR and other regulations. The industry must adjust to provide consumers with the information they need to make an informed choice, while directly challenging consumers’ apathy. Advisers must develop skills and embed processes that enable them to present consumers with all the information necessary to make a sound judgement, in as simple manner as possible. Through an awareness of Behavioural Economics, and greater training and development, the industry can ensure advisers have the knowledge and skills to open the finance world to clients and consumers. The best way to dispel the Ambiguity Aversion is through increased clarity.

Anchoring – People have a tendency to latch on to one of the first pieces of data they receive. This is known as the ‘anchor’. All future information is compared to this anchor and the final judgement and decision is often weighted towards this figure. Even if you later provide clients with evidence that should totally supersede the anchor they are often reluctant to let go of this first data point. Advisers must be careful how they present data to clients and be prepared for clients to pick an anchor that was meant as an offhand remark. You may need to play devil’s advocate and query the client’s choice of anchor to help them truly evaluate the relevancy of a particular piece of data.

In our industry, it is common that consumers begin their research by asking friends or colleagues before contacting an adviser. Thus anchors are often established in these initial conversations. On discovering that a colleague pays £200 a month into their pension scheme, a client may latch on to this amount as their gauge for a ‘reasonable’ payment. When their adviser, after assessing their particular situation, age and expectations, suggests a payment of £800 per month the client may baulk. Even when the adviser explains that this figure both reflects the client’s increased expectations and their tardiness in taking out a pension scheme, the client may find it difficult to let go of the initial anchor. They may continue to compare every option to this first, unrealistic anchor.

Availability – People often turn to the availability heuristic when judging the probability of an event. People compare data to their own experience or knowledge regardless of whether this is universally common. For example, if an individual knows several people who, having taken out a mortgage with a particular provider, had their home repossessed, they may think this is a highly likely outcome of borrowing from this particular provider. They effectively blame the provider as their experience suggests the provider has an ‘unreasonably’ high repossession rate. Even if an adviser were to show them genuine data proving that the firm’s repossession rate is in fact below average, the conservatism heuristic may lead them to undervalue the genuine data.

The availability heuristics is also true for time. In the same way that after passing a road accident we become on our guard for further accidents ahead, after seeing news of an internet security breech at one bank, consumers may be very much on their guard in relation to that, and possibly other, banks in the days that follow. They may take this view without any knowledge of the respective banks’ security systems or what caused the breech. This worry is purely caused by the fact that this data is currently readily available and much discussed. In 2 months’ time, the same individual may consider internet security much less important when choosing a bank. It is important advisers get to know their clients, seek to understand their worries both short and long term and assuage their doubts helping them to see a much broader perspective.

Conclusion

The judgemental heuristics that affect people’s perceptions should not be unfamiliar in concept to our readers. Most people will recognise their own behaviour in the majority, if not all, the heuristics mentioned above. However, in the past, many within the financial services industry have failed to recognise fully that people deploy these heuristics when judging financial products. While our processes and sales styles have subconsciously flexed to accommodate these heuristics, we have clung on to the logic and consistencies implied by neo-classical economic theory, i.e. the false impression that full disclosure of all the relevant information will naturally lead to sound judgements and good decision making. With a better understanding of Behavioural Economics, organisations and individuals can consciously adjust their processes and techniques to robustly challenge poorly formed judgements and guide clients through financial decisions in a manner that works with, rather than against, people’s natural intuition.

Once we have covered all relevant aspects of Behavioural Economics, the final two sections in this guide will provide readers with further details on how we recommend organisations and individuals adjust their approach to aiding and influencing client decision making.

This section has touched on one aspect of Behavioural Economics; judgement and perception. The next section shall dive deeper into the effects of framing, with specific emphasis on Loss Aversion. For more information on Behavioural Economics please email enquires@bigrockhq.com.

2) Emotions & Framing

Forming, Influencing & Overturning Belief

Traditional economic theory presumes practitioners, clients and consumers act purely from self-interest to maximise their own gains. It ignores the influence of prior experience, moods and emotions, such as fear or regret. Yet society shuns the notion of emotionless decision making, portraying those characters from popular fiction who rely purely on logic as at best strange (Spock and Sherlock come to mind) and at worst evil (Daleks). While it is widely accepted that emotional responses can be a weakness when making decisions, the majority agree that it is a key component of our humanity and can also be a great strength. Many individuals and companies give money to charity, despite there being no immediate benefit. Similarly, many would choose to invest in a family member or friend’s business because of their personal connection, despite better investment options being available.

This human aspect to decision making is something we are all aware of. However, while Behavioural Economic theorists accept the effect of emotions as an important part of decision making, historically they have largely neglected this field, focusing scholarship on judgemental heuristics and cognition (explored in the first section). Jon Elster argues that this is largely because the ‘founding fathers’ of Behavioural Economics, Tversky and Kahneman, were “outstanding practitioners” in cognitive psychology. There were no theorists of a similar calibre promoting the effects of emotion on economic decision making, in those early days. Yet, understanding the effect of emotions on decision making and how the way you frame an option can trigger emotional responses is a key element of guiding and influencing consumers’ opinions and decisions. Otherwise, the unwary can be blocked by a ‘bad feeling’ that even the client is unable to fully articulate.

Perseverance

Psychologists have found that once an opinion is formed people become ‘sticky’ in their beliefs. Emotions are particularly affected by the Conservatism heuristic (where people underreact to new evidence). If an adviser makes a negative first impression, this opinion can be very difficult to overturn even when the client is presented with numerous examples of their competency.

Furthermore, people like to align their decisions to previous beliefs. If an option can be linked in some way to a common principle that drove a previous decision, it is as if the decision before them has already been made. If a client has previously been advised that the best option for their pension is to spread their investment amongst multiple funds, they may apply the same principle to their day to day banking, spreading their savings across multiple accounts. Clients effectively anchor this decision to a previous belief driven by an old emotion that may no longer have relevancy.

Thus, it is important to recognise and try to understand the ‘emotional baggage’ a client brings to the table. Advisers must also be wary of how the way they frame particular options might trigger certain emotional reactions.

Emotions & Moods

Psychologists have found that people’s immediate emotions and mood have a significant effect on their attitude to risk and how they form opinions and ultimately make decisions. Generally speaking those in a happier mood make more optimistic choices, while those experiencing anger or grief are far more pessimistic. Those feeling happier tend to be more adventurous and more prepared to explore new ideas. Those in a more negative mood tend to rely more on their usual rules of thumb, relying on heuristics that have helped them make decisions in the past.

After researching over 25 international stock exchanges, Hirshleifer and Shumway found higher stock returns were seen after morning sunshine. They argue that because people are more optimistic on a sunny day, they are more inclined to buy stocks.

A client in a happier mood may be more inclined to consider new investment options or to back a new business venture. For instance, those involved in intermediary sales may find that an IFA in a good mood may be more inclined to consider the benefits of a new product. However, an IFA experiencing more negative emotions may insist on simply brokering a deal around those products they have offered their clients before. It is also worth noting that with intermediated deals there are two sales, two people (the IFA and their customer) and thus two sets of emotions that won’t necessarily be aligned.

Emotions can be categorised as follows:

- Social Emotions: anger, hatred, guilt, shame, pride, admiration and liking

- Counterfactual emotions generated by thoughts about what might have happened: regret, rejoicing, disappointment, elation

- Emotions generated by what may happen: fear and hope

- Emotions generated by things that have happened: joy and grief

- Emotions generated through comparison with others: envy, malice, indignation and jealousy

- And finally those that don’t easily fit into a particular category: boredom, love, surprise, worry, desire, etc.

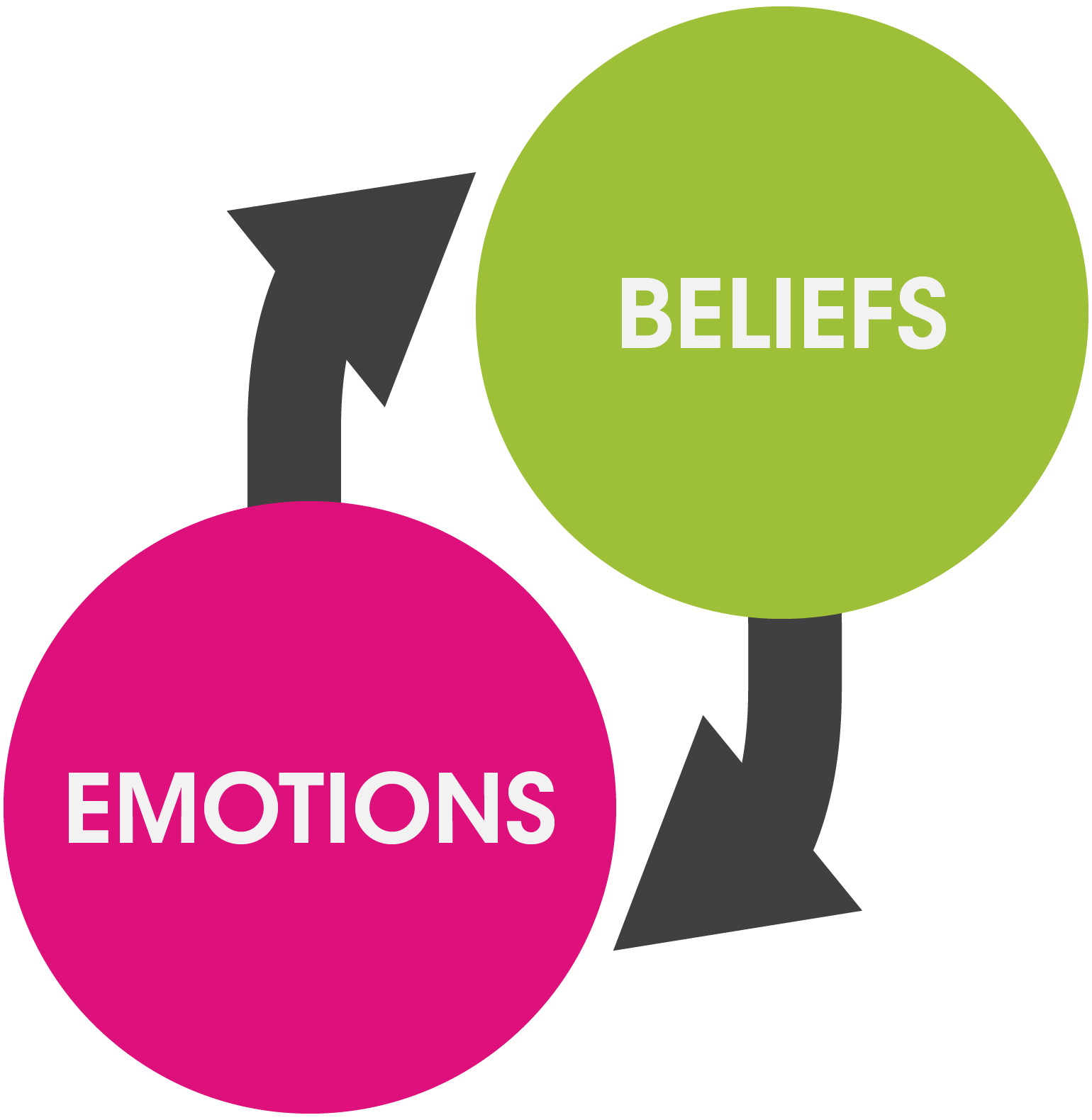

What is true of the majority of these emotions is, while they help us form opinions, they are also generated by the beliefs and opinions we already hold. These beliefs nuance exactly what we feel in response to the information placed in front of us. For example, if a client, after being rejected for a small business loan, believes that their lucrative business plan has been unfairly rejected they may feel anger. However, if they believe that that particular provider rejects all business plans from their particular industry the emotion may be closer to indignation. If they begin to doubt their business plan, they may begin to fear they will not be able to secure a business loan at all. This may drive them to pursue a new course of action or blame their adviser for not preparing them for this possibility.

Below, we illustrate how an emotion can be broken down, using Jon Elster’s theory of emotional responses. Not all of the emotions listed demonstrate every characteristic. However, each element is a recognisable and common cause or response to emotions. It is helpful to examine this cycle in detail to enable us to contemplate how practitioners can identify and influence clients’ and consumers’ emotional responses, opinions and beliefs.

Cognitive Antecedents

Emotions are triggered by our beliefs.

Example: An investor in Tech stocks in the early 2000s may have believed they would get a good return on their investment, but then lost out when the bubble burst

Intentional Objects

The emotion is targeted towards a thing (an object, a person etc.).

Example: Facing the evidence of their loss the Investor may feel anger or regret. This emotion is likely to be targeted towards a particular thing, e.g. their adviser, the tech company, or even envy towards a friend who managed to cash in while there was still a profit to be made.

Physiological Arousal

This can result in a hormonal or nervous effect ( e.g. pang of emotion, hot flush, adrenaline rush etc.).

Example: The emotion may trigger a physical reaction. Their stomach may turn over. They may feel a pang of regret. Etc.

Physiological Expressions

This can result in a change in posture, facial expression, voice tone etc. some of which are more controllable than others

Example: The investor may then raise their voice at the adviser or begin pacing around. Their facial expression is likely to change. Or they may try to hide their emotions.

Valence

How the emotion rates on the pleasure-pain scale. Whether it is a positive or negative feeling

Example: In general, a high physical arousal will result in a strong emotional feeling. This is linked to the importance of the cognitive antecedent and the object. If the investor had been a strong advocate of this approach and had advised their friends to invest (Cognitive Antecedent) or if the loss were great (Intentional Object) they are likely to feel stronger emotions and display a greater reaction.

Action Tendencies

A “state of readiness” that will lead to a decision or action. We form an opinion or belief based on our emotion that drives us towards an action.

Example: The feeling might then drive an illogical response e.g. selling all their stocks and shares in every industry for fear of a similar result. It could also form the basis for an opinion that may go on to affect future decisions. E.g. the investor may form the opinion that tech stock is not a good investment, sticking with this belief for years, even decades to come.

Emotions as an antidote to Procrastination

While emotions can hinder interactions with clients, consumers and colleagues, they can also accelerate the decision making process. Some theorists believe that emotions have evolved to help us make decisions where our inability to rationalise the options could leads us to procrastinate and avoid the decision all together. We won’t necessarily make the best or most rational decision but we will at least be prompted into making some sort of a decision.

For instance, a customer struggling with debt may be unable to rationalise the options available to them. A purely rational being would then be able to take no actions at all. However, emotions like fear and guilt may lead them towards taking some action, thought it may not be entirely thought through. It is the duty of the industry to provide consumers with clear information so that they jump towards the right decision (e.g. talking to their bank) rather than the wrong decision (e.g. approaching a pay day loans company or taking out another credit card).

This phenomenon can also occur in the B2B arena. Even though understanding of financial concepts is often far more mature within a B2B relationship, we are still dealing person to person. In a corporate pension’s pitch the decision maker may feel overloaded with information and may not have fully grasped all the points need to make a rational decision. However, emotions including envy at the deal he believes a competitor made, or even boredom at having sat through one pitch and not wanting to sit through another, may drive the client towards an opinion or a particular action. This opinion would be formed, despite them not deploying the full cognitive process.

The Legacy of Emotions and Moods

The consequences of our opinions and beliefs long out live the emotions and moods that formed them. Specific emotions usually fade within minutes and moods within hours or days. The happy mood that drives a client to invest in a particular stock will have long faded by the time a return is made. Yet clients will be left with the opinions they have previously formed based on the original emotional reaction. For instance, as illustrated on p. 7, a client that lost out when the Tech bubble burst in the early 2000s may have felt intense anger, regret or indignation at the time. These emotions may have driven a belief that all tech stocks (or even all stocks) are too high risk. This opinion could have persisted for years after the original emotion was felt and will so influence future decisions and emotional reactions.

Framing – A Case Study on Prospect Theory

As discussed above (when considering emotions as an antidote to procrastination) emotions have a particularly strong impact on decision making when little is known or understood about the respective choices. People often form an opinion ‘in the room’ based on the emotions stirred in that moment. This makes decisions extremely sensitive to presentation and context. It is important practitioners are aware of the presentation and influencing techniques they can use to nudge consumers, clients and colleagues towards the right decision; how they can frame the options to lead the listener to the best possible option. The deployment of such skills will be covered in the final section. Here, we shall examine how framing a choice as either a loss or a gain affects our opinions and choices. This is known as Prospect Theory.

Prospect Theory:

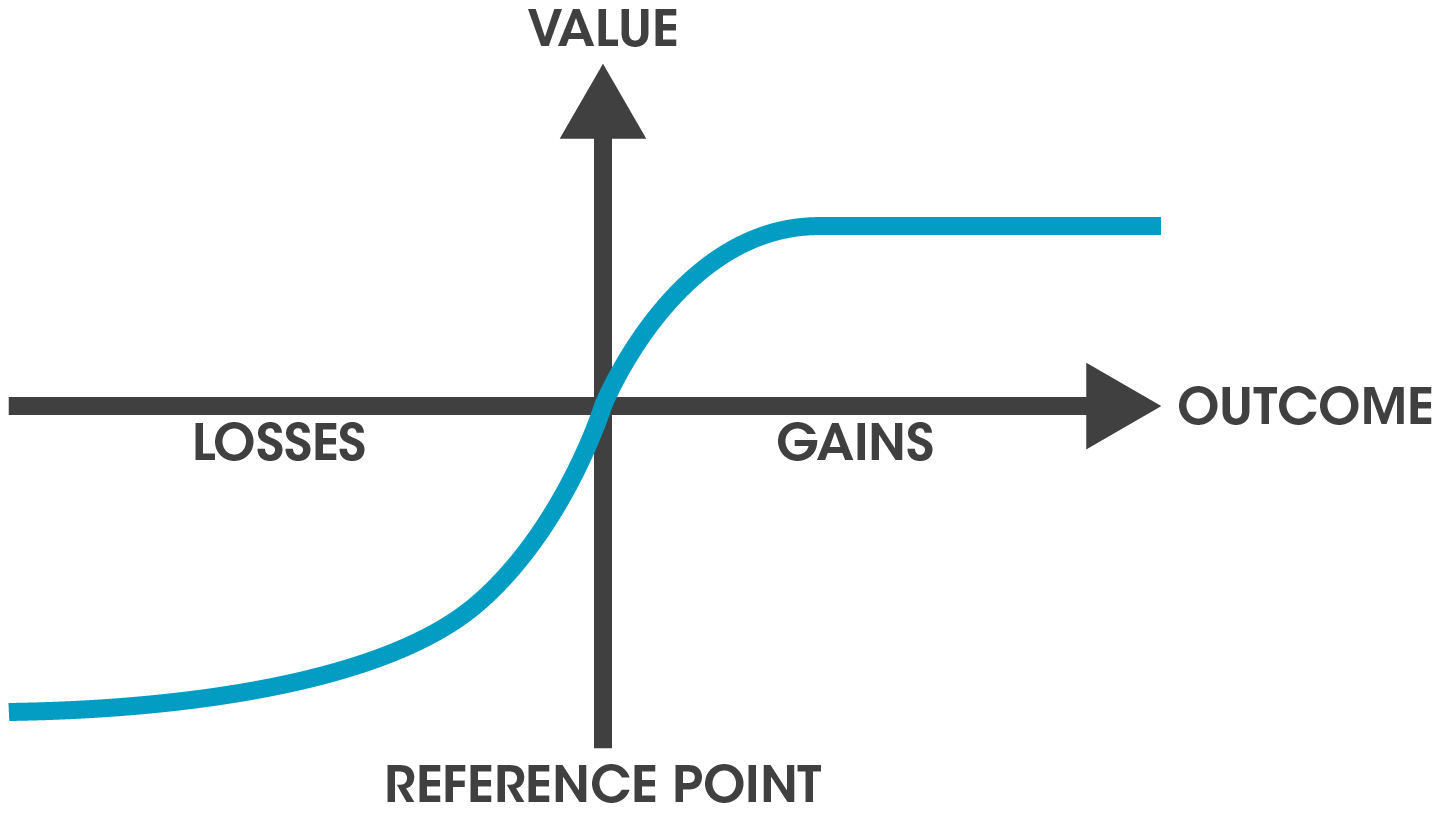

Our emotional reaction to the idea of gains and losses, mean that the way a figure is positioned is often more relevant than the final value. Traditional economic theory would suggest that the net losses and gains would be weighed up, and then the rational being would opt for the most likely chance of the highest gain. However, in reality people react emotionally to the prospect of losses and gains. For example;

When 150 people were given two choices, one between favourable prospects and one between unfavourable prospects, they responded as follows:

Asked to choose between:

A. A sure gain of $250

or

B. A 25% chance to gain $1000 and 75% chance to gain nothing

84% went for A, the smaller positive certainty, while only 16% went for the potentially more lucrative risk, despite the fact that economic theory dictates we should view them as equal choices.

Then, asked to choose between:

C. A sure loss of $750

or

D. A 75% chance to lose $1000 and 25% chance to lose nothing

13% went for the certain loss (Option C), while 87% were prepared to gamble on the chance of losing nothing with option D.

In fact, A and D provide the best rational option. Yet, the framing of the question tricks the brain in to seeing the other options as more favourable. People are willing to settle for a reasonable level of gain (even if they have a reasonable chance of earning more). However, they are prepared to accept a risk where they can limit their losses. Losses are weighted more heavily than an equivalent amount of gains. Theorists suggest that this is caused by the tendency to hold on to a small gain and the desire to counteract a small loss. It is linked to the gambler’s fallacy heuristic, the mistaken belief that chance will correct itself in our favour. That eventually we must win back our losses.

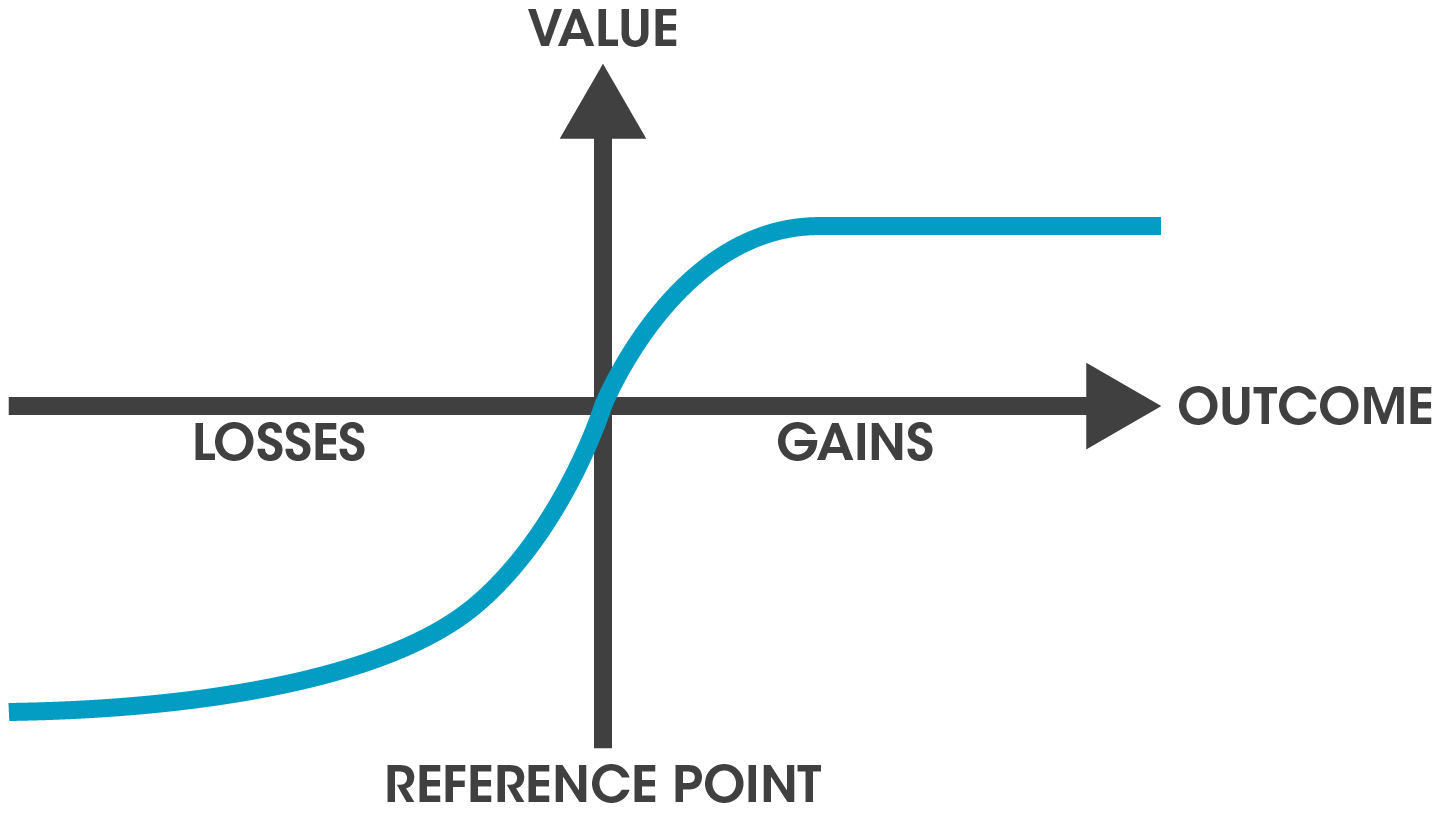

As discovered by Tversky and Kahneman, our reactions towards gains and losses follow the trend indicated in the graph on the right. When an option is positioned as a gain, for low value options we are disposed to take risks but the more we feel we have gained the more inclined we are to avoid risk. Hence the graph straightens out as the potential gain increases. However, when it is positioned as a loss, we are initially more conservative before becoming increasingly risk seeking, as we look to make up our losses. As such the loss curve does not level off to the same extent.

Relevancy

This phenomenon has the following effects:

Disposition effect – Investors tend to hold onto losing stocks for too long, taking a high risk option in the hope that the stock will improve. They also tend to sell winning stocks too soon, taking a risk avoidance attitude, cashing in on their success out of fear that they will lose what they have gained. This behaviour is regularly observed, despite the fact that the most logical course of action would be to hold on to winning stocks in order to further gains and to sell losing stocks in order to prevent escalating losses.

Poor allocation of resources – As our reactions and opinions can vary depending on how a choice is framed, it is common that people can apply risk adverse behaviours in one situation and risk seeking behaviours in another. This can result in them paying a premium to avoid risk in one area, while they are seeking risk in other areas of their finances. In an organisation, one division may be facing a negative choice so naturally go for a risk seeking option, whereas another division may be facing a positive alternative and so be risk averse. The organisation would be better combining the choices and going for a risk neutral option. It is the adviser’s responsibility to ensure clients view their finances as a whole. This tendency will be explored further later.

Perceived Outcomes – People tend to feel worse when their actual gain is less than what they perceive they could have achieved. For example, if the top prize in a competition is £100 and a contestant wins £50, they would feel worse than if the top prize had been £50. They feel that they have somehow lost out, because or the circumstance of their winnings… because there was the chance for more.

In a pensions context, if a client was told their pension would be worth £100k when they retire and in fact in turned out to be worth £80K they may feel they had lost out. However, if they had been told their pension would be worth £60K, the extra £20K would be seen as an added bonus. Frustratingly, as many advisers will have experienced, the feeling of happiness generated by the gain of an extra £20K, is not equal to the negative emotions generated by the perceived loss of £20K.

Comparing Alternatives – When a choice is framed as a choice between a neutral options or a gain the tendency to prefer the gain is much, reduced than if that gain were presented in terms of a loss. For example, in the scenario of considering insurance providers, if one provider offers a cash lump sum of £100 pounds:

One advisor, Jack, may say: “Policy B offers a cash lump sum of £100, which Policy A does not.”

Whereas Jill may say: “If you opt for Policy A you will be turning down £100”

Jack presents it as a gain and it seems like a nice extra but may not sway your decision. Jill presents it as a potential loss and it seems foolish to opt for Policy A over Policy B.

Even those with a strong understanding of statistics are susceptible to prospect theory. It’s not about the risk itself but the way it is framed. Thus practitioners must be careful how they present solutions. They must seek to present the most rational option so that it becomes the most obvious human choice.

Similarly it is easier to forgo a discount than accept a surcharge, as a surcharge is seen as a loss (someone is unfairly charging more) whereas a discount is seen as a gain (a lucky win). For this reason it is said the Credit Card Lobby insist that any price difference between cash and card purchases should be labelled a ‘cash discount’ instead of a credit card ‘surcharge’.

As such practitioners should take when framing options as losses or gains.

If you were looking to attract a risk adverse choice e.g. convincing a client to stay with your firm then it would be best to present the option as a gain. Hence the popularity of loyalty schemes in the FMCG industries. Conversely, if you were looking to nudge clients towards a risk seeking choice, e.g. switching to your services, you should frame the choice in terms of losses.

Conclusion

As the FCA’s interest in the firm’s ethical culture and the impact on behavioural economics on the financial sales process increases, it is ever more important that practitioners develop their ability to recognise clients’ and consumers’ emotional reactions, how this can impact the sale and how they can nudge their audience towards the right action by the way a decision is framed. The FCA is looking to firms to take responsibility for the way they frame the options they put to clients.

In his recent speech to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, FCA Chief Executive Martin Wheatley, gave the following example from his experiences in his previous role in Hong Kong:

“There, individuals who had term deposit accounts maturing were invited to meet the bank manager – the banks would then offer them a new deposit rate paying 1% or an alternative ‘safe’ product paying 7%.

‘Why does one pay 7%?’ was the question that consumers didn’t ask. They didn’t because it was offered to them by their bank and they trusted that the bank wouldn’t sell them a ‘risky’ product.

Had they known the 7% product was a complex structured product that was effectively writing credit insurance, they might have thought twice. But the product was so opaque consumers didn’t know the right questions to ask.”

It is now the industry’s responsibility to frame the options in the right way, to elicit the right questions and to ensure clients truly understand the options in front on them. At the same time though, practitioners must be aware that clients are unable to compute too much information at once. That our mental capabilities are not as complete as implied in traditional economic models. As such practitioners must provide clients with the right choices, framed ethically to raise the right emotional reaction to secure the best possible outcome for all involved.

The third section shall explore the limits of our cognitive power in more detail, after which we explore the opportunities for organisations and individuals to develop their culture, processes and skills in light of what we have learned on this topic.

For more information on Behavioural Economics please email enquiries@bigrockhq.com.

3) Cognitive Limits

Consideration & Cognitive Power

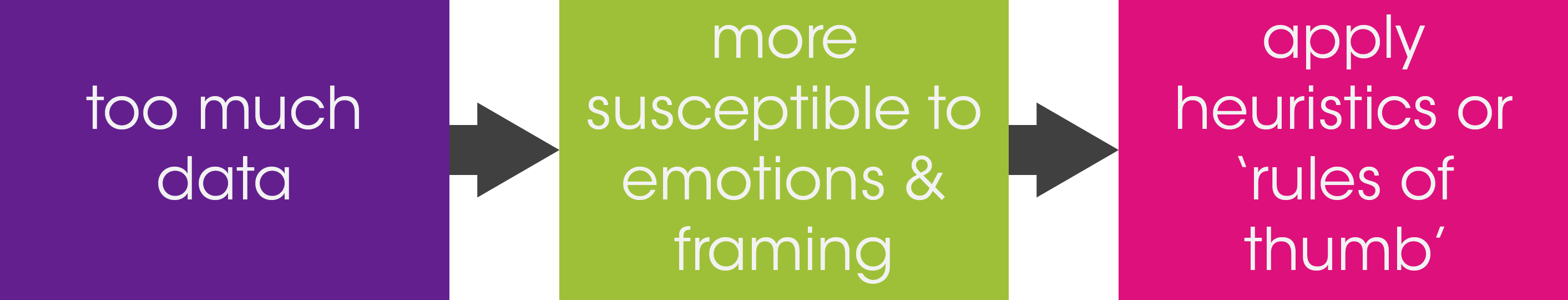

Behavioural Economics theorists have shown that the human mind has a limited capacity for absorbing and analysing information. We all have limited computational and recall capabilities, so cannot process an unlimited amount of information.

Miller’s Law

Psychologist George A. Miller found that the maximum amount of information a human mind can hold in working memory is 7, plus or minus 2.

Miller’s Law: 7 ± 2

Miller found that people’s capacity to compute information effectively was almost perfect when only considering 5 or 6 ‘chunks’, but when more were added their memory failed them.

Yet, what a ‘chunk’ means depends on each person’s knowledge. The more you know on a topic the more you can condense information into a specific chunk. For example, when learning Morse code, beginners initially compute each dot or dash as 1 chunk. However, as they learn the code for particular letters, each letter becomes 1 chunk. So with experience, they are able to understand and translate more of the code at once. They are still only using about 7 chunks, in line with Miller’s Law, but as their understanding and knowledge increases the chunks grow larger and they are able to process the information much quicker.

Advisers should bear in mind that while they may be able to discuss 5 or 6 particular aspects of a financial report, their client may be dividing each of these aspects further and may feel swamped by information. When considering investment options, an adviser may group the investments in to Bonds, Shares, Managed Funds and Alternative Options. However, their client, with little knowledge of this field, may be unable to follow a discussion framed in this way. They may see each type of Bond available as one ‘chunk’. Advisers should be aware of how much information the client feels they are being asked to compute and try to help them assimilate particular elements into one chunk, if the discussion is extensive.

When tasked with computing more information than they can handle, people revert to heuristics, which often don’t take into account every aspect of significance to the final outcome. When asked to choose among many alternatives, unable to weigh all the advantages and disadvantages of all choice options, we make a selection by sequentially eliminating alternatives that do not possess certain characteristics. This may lead clients to dismiss an option because it does not offer a particular benefit; even though, given all its other advantages, it may be the best choice. For instance, a corporate client presented with a large number of employee benefit packages, may decide to eliminate all those without a cycle to work scheme. This may eliminate options that fulfilled all their other criteria, leaving them with options that do have a cycle to work scheme but with few of their other requirements. Advisers must work to guide clients through their decision process, condensing information into sizeable chunks and working to understand and mitigate the effects of any heuristics the client does deploy

Time and Patience

Traditional economic theory has presumed that human beings will have unlimited time and energy with which to make their decision. However, the reverse is often the case. Many clients and customers have ‘better things to do’ or far greater distractions playing on their minds. Advisers should be aware that, even when clients request a meeting, their future financial situation may not be a top priority. A Director considering investment options may be worrying about another meeting he has later in the day and may not be using his full attention to analyse the data provided. Consumers who call their bank’s contact centre or drop into a branch may have a limited time to discuss their options. Furthermore, many Consumers have little option but to bring children along to financial meetings. This can result in a rushed discussion, where clients fail to fully grasp the options and so either put off the decision or make the wrong choice.

Umpqua Bank in Seattle have gone out of their way to create regional branches, or ‘stores’ as they call them, where people feel comfortable, relaxed and able to stay to discuss their options in full.

Mental Accounting

Our limited ability to compute a wide amount of information at once, often leads people to compartmentalise data so that they can dismiss a particular ‘chunk’ as irrelevant to the decision immediately in front of them. This is known as Mental Accounting.

Behavioural Economics theorists have found that people tend to interrogate decisions in a narrow fashion, concentrating on the decision in front of them. If choices come one at a time, people tend to consider each option on its own merits, with little reference to previous decisions. However, if asked to make several choices at once, it is more likely that the decision will be interlinked. For example, if presented with share options in the company they work for as part of an internal review, many employees will consider these on their own, with little reference to the other investment options available or to the impact this new share will have on their current investments. If they think of their share options as part of their employee benefits or pay, they may completely separate this investment to those made privately with their partner, or those they discussed with their IFA as part of their pension. However, if the employer asks a financial adviser to provide broad advice for their employees and the adviser, as part of a wide investigation of the pension, investment and savings options available, highlights the benefits of the company’s shares, the employee is likely to make a more balanced choice. They are also more likely to select several related investments, than just opt for one share option.

Mental accounting means that very few people consider their entire net worth at once. The majority will mentally hold a bit back, earmarking a particular sum for something else when considering their finances. We effectively set up different mental accounts or budgets for different outcomes. We may think of a certain sum as ‘holiday money’, ‘leisure money’, ‘food money’ or ‘Christmas savings’. This can lead people to run up a debt on their credit card, which they use to cover household bills, despite the fact that they have money going out into a pension where they are aware they could freeze payments for a year. The interest lost by freezing their pension for 12 months is much less than the amount lost in interest on their credit card, especially if they continue to be unable to pay their debt off. It is important for advisers to gain a full understanding of how their clients compartmentalise their money. Advisers must ensure they engage with clients to elicit a full picture of their financial situation.

Many retail firms have harnessed this phenomenon to help online customers manage their money. Many banking apps enable customers to rename and set goals for their savings accounts. This helps the bank and the customer compartmentalise their money in the same way, enhancing the customer’s experience and enabling the bank to provide an excellent service and encourage consumers to save in the most efficient way..

Enabling consumer’s to customise their accounts in this way can be very powerful. Theorists, Cheema and Soman found that when very low income parents placed their savings in an envelope labelled with a picture of their children, their savings rate nearly doubled.

Mental Accounting is also evidenced on a corporate level. A corporate client considering asset management options, may earmark certain assets for particular use, separating those assets they wish to manage from particular funds earmarked for employee pensions or compartmentalised as ‘the office premises’.

Mental Accounting also explains some of the popularity of ‘add on’ products. As Martin Wheatley explained in a recent speech to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, when being sold add on products, people place them in the same ‘mental account’ as the main product, often not bothering to even research other options. Wheatley explained how, working with academics from University College, London, they designed an experiment where participants were asked to hunt for a main product (a holiday, car or tablet, etc.) and were then given the opportunity to buy related insurance products at various stages of the buying process:

“For standalone insurance with a single price there were almost no mistakes in choosing the best deal … When it came to comparing offers with prices for a main product, as well as a separate price for an add-on without a total, we start to see problems emerge. One in five participants here could not identify the cheapest combination.

At this point, we tested the impact of transparency. So, the add-on was only unmasked, if you like, when the individual had started buying the main product. Unsurprisingly, these ‘point of sale’ offers had a more powerful impact on consumer behaviour than selling add-ons transparently.

So, compared to a standalone insurance purchase, consumers were four times less likely to shop around for insurance. In fact 65% did not look at any alternatives at all before buying and were six times more likely to make mistakes.

Also clear, within all this data and detail, is the significance to sellers and buyers alike of framing. So, when monthly prices for an annual policy were presented to consumers, instead of the total cost for the year, there was more confusion about the cash outlay, with less shopping around; higher prices paid; and larger losses made.

All of which tallies with our broader understanding and analysis of the industry numbers we’ve been crunching over the last year. Around 25% of consumers who bought add-on insurance were not aware they could buy it separately elsewhere. 58% did not make comparisons with other policies on the market – compared to 22% of standalone buyers. And around one in five could not remember buying the product three months after purchase. On top of this, we see claims ratios falling below acceptable levels: Guaranteed Asset Protection insurance at 10%; personal accident at 9%.”

In the experiments cited, the way the insurance was presented as an add-on to the main purchase led consumers to link the validity and economy of the insurance to the product they were buying. It seems they believed that as the main product offered the best deal, so would the associated add on. Thus mental accounting is one reason why so many consumers fell victim to the miss-selling of PPI.

Finally, evidence suggests that people don’t just compartmentalise information based on how they intend to use it. Money may also be grouped by its source. For instance, a client who has just been awarded a large bonus may treat this money differently from other earnings. While, they may usually put their excess earnings towards their mortgage, they may be more tempted to treat themselves to a holiday (as they clearly deserve it) or invest the money in company share option (to reflect their gratitude and loyalty to their employer). Similarly a business may view the money borrowed from an early investor or bank loan differently to the money earned from a successful project with a new client. Again, advisers must look to elicit a full understanding of their client’s situation and the emotional significance of particular accounts. While logically money should all be viewed equally, regardless of source; in reality, as we saw when examining Prospect Theory, we develop different emotional connections to money earned, money found, money lost and money gained.

Prospect Theory – Further Examples

In the previous section, 2) Emotions & Framing, we provided a case study on Prospect Theory. Prospect Theory states that our emotional reaction to the idea of gains and losses means that the way a figure is positioned is often more relevant than the final value. Traditional economic theory would suggest that the net losses and gains would be weighed up, and then the rational being would opt for the most likely chance of the highest gain. However, in reality people react emotionally to the prospect of losses and gains. Tversky and Kahneman found that when making a choice where the outcome was uncertain, if the option was presented as a possible gain, we are less disposed to take risks. However, if the option is presented as a possible loss we become more risk seeking.

Investing and Managing Wealth

The effects of Prospect Theory can be extremely frustrating for those within our industry who seek to advise on and /or provide investment options, in the client’s best interest. Any gains made for clients are likely to be given less weight than any losses incurred. Furthermore, the disposition effect means that clients tend to hold on to a losing stock, risking more than they would for a gain, in the hope that they will recover their original investment.

Investment advisers must tread a fine ethical line. As consumers’ attitude to risk is illogical, or at least unequal, it may be in the client’s interest to frame an investment option in terms of what they would lose if they missed this opportunity, rather than as what they had the potential to gain.

Furthermore, advisers have to be careful that the judgements and advice they pass on to clients isn’t effected by prospect theory. Adviser should constantly question whether their perception of a particular investment is fair or influenced by loss aversion. Then they must ensure that they are presenting their recommendation in such a way that the client will recognise it as the best option.

Insurance

The insurance industry also faces a challenge in this area. Consumers purchase insurance to protect themselves from losses. They expect little direct gain from their purchase (except perhaps greater customer service or extras like breakdown assistance with car insurance). Thus insurance is bought with losses in mind. This could swing either way, depending on the thought process of the individual. Consumers may be prepared to risk a loss and not invest in insurance. However, if the adviser frames the options in terms of the current gains the consumer stands to lose, they are likely to invest greatly in reducing that risk.

For example, a business owner may feel that extensive insurance is unnecessary. However, if the adviser explains that the businessman may stand to lose the blossoming business they have built if they don’t have insurance to protect them from such an eventuality, the client is highly likely to take a different view. In this sense, the adviser is framing the insurance product as a way of reducing the risk on the consumer’s ‘gain’, the gain being the successful development of their business. The consumer is not willing to risk the gain inherent within their business and so is persuaded to invest in protection.

Corporate Competition

People consider losses as far more important than gains. This can be hugely important in corporate bid situations. If your solution has features not offered by your competition it is far more beneficial to present these as things the client would lose by going with another provider, rather than as additional benefits they would gain by opting for your solution. In such situations, those pitching first have the advantage of setting the standard. If you can position the benefits of your solution as what the client truly needs, as a complete solution to their requirements, any competitor with an additional benefit, but without one of your added features, may lose out. You have convinced the client that by not going for your option they would lose something of value, a highly emotive condition. Yet, any benefits provided by your competitors are simply gains, a happy extra but not as crucial as the outcomes of losing your feature. Thus an understanding of prospect theory can be highly useful those involved in sales, pitching or who regularly engage and do business in the corporate world.

Conclusion

As financial advice becomes ever more exclusive and consumer’s experience lessens, it is increasingly important that firms develop clearer and more ergonomic forms of communication with their clients and customers. The FCA is conducting a more

holistic approach to regulation, in the hope that this will enable the industry to provide sound, ethical and significantly condensed financial information that will aid and not hinder consumer’s understanding, while facilitating their buying process.

While this approach by the regulator may ease communication, it also places greater responsibility on firms to understand and respond to consumers’ buying process. As such a full understanding of Behavioural Economics is increasingly important. Advisers, who can understand client’s, and indeed their own thought processes and cognitive limitations, are more likely to provide clients with the right amount of information and lead them to the most suitable decision have a distinct advantage. In effect they will provide the best consumer experience and lead clients to the best possible option, a recipe for mutual success. As such, the ethical application of Behavioural Economics theories is both compliant and profitable.

The final two sections will provide advice and guidance on how firms and individuals can apply these theories for the benefit of consumers. The rest of this series explores the opportunities for organisations and individuals to develop their culture, processes and skills in light of what we have learned on perspectives, heuristics, emotions, framing and our cognitive limits.

For more information on Behavioural Economics please email enquiries@bigrockhq.com.

4) Corporate Change

Introduction

In earlier sections we explored how these phenomena can affect Financial Services professionals’ conversations, interactions and on-going relationships with clients and consumers. Now we shall look to provide organisations with a strategy for understanding how these phenomena impact their client’s experience and how they can begin to construct a change programme to improve this. In this section we challenge you, the reader, to reassess your company’s customer journey, in light of what we now understand about heuristics, emotions, framing and the weaknesses of our cognitive processes when compared to traditional neo-classical economic thought.

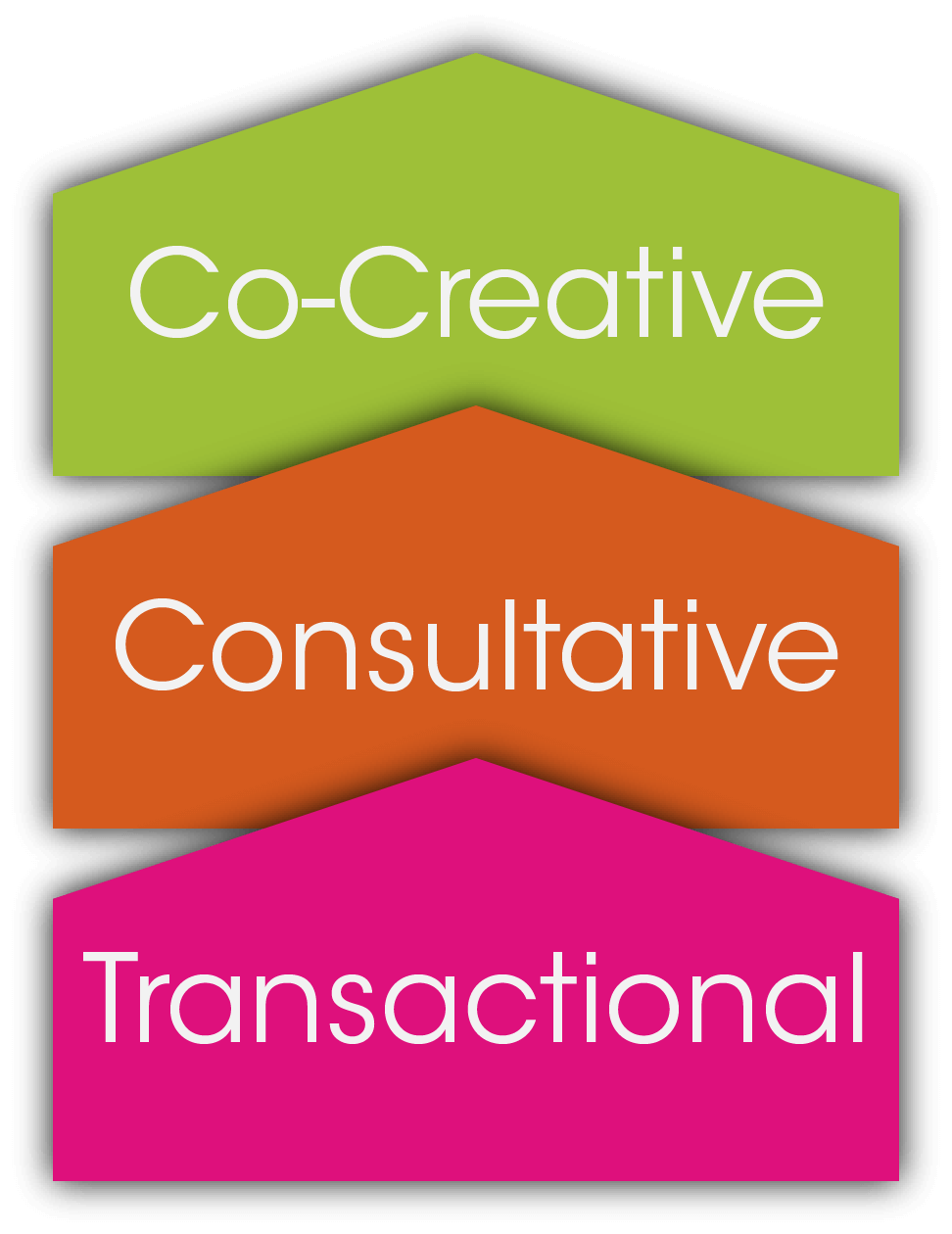

Embracing Behavioural Economics is a complex task for any organisation. The theories have implications for every aspect of a business from product creation to pricing, from national advertising to the look and feel of particular branches to the sales processes used by your telesales teams, even internally from your remuneration policy to your leadership and management strategies. Here we will concentrate on the effects Behavioural Economics phenomena have on the experience your clients and customers have with the people in your firm, in the relationships you build with customers and the customer journey. Here Bigrock’s expertise is strongest and it is in these areas, where employees are in direct communication with customers and can so easily stray outside of process, that we believe conduct, compliance and commercial outcomes are most at risk. Yet we urge the reader to consider the wider implications of Behavioural Economics within your firm and the industry as a whole.

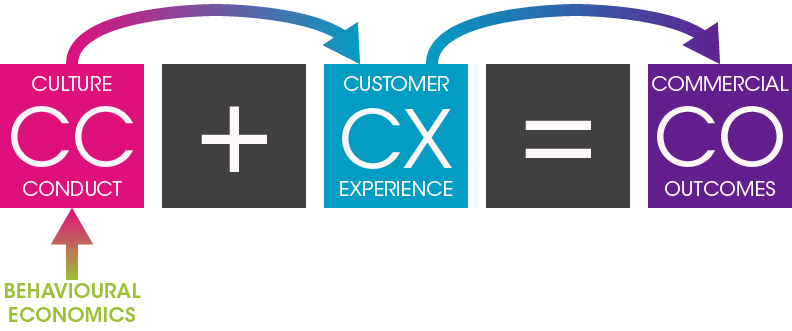

The following ‘equation’ shows the deep relationship between culture, compliance, customer experience and exceptional commercial outcomes:

Strong culture and excellent conduct adds to your client or customer experience to drive greater commercial outcomes, including increased profits and customer delight.

Your future compliance strategy should draw on Behavioural Economics phenomena, in line with the regulators advice, to ensure colleagues apply best practice techniques with consistency and have the skills, knowledge and processes to adapt to each situation and the specific heuristics the client applies.

In many cases conduct and culture models have been formed using neo-classical economic assumptions (as discussed earlier); for example, that people can analyse an unlimited amount of information resulting in a client experience where clients are flooded with compliance information, in effect completely paralysing their decision making process.

Yet it is not as simple as adapting your existing processes for the ‘Behavioural Economics model’. No such model exists. In earlier sections, we demonstrated how the different heuristics contradict each other, how the path taken by consumers and colleagues will depend on their emotional state and previous experiences, and how knowledge and intelligence influences how much information we can retain and use to make a decision or form a judgement. Different people will apply different heuristics at different times on different occasions, dependent on a whole range of factors.

So how can an organisation possibly utilise Behavioural Economics effectively?

Organisations must ensure that all client facing employees have a thorough understanding of Behavioural Economics, have the skills to recognise where heuristics are being deployed, adapt their approach accordingly and even explain the phenomena to clients where appropriate. The final section will explore these skills in more detail. As well as educating employees, organisations can assist them by mapping the customer journey and identifying likely hot points where Behavioural Economics phenomena are most likely to come into play. To do this, we recommend organisations follow the following 5 step discovery and change process:

- Understand Behavioural Economics (BE)

- Understand your Customer Experience (CX)

- Decide how your ideal CX would incorporate BE

- Identify the gaps between your current CX and your ideal CX

- Change!

In this section we shall explore each of these steps in turn, challenging you to apply them to your organisation.

An Aligned, Values Driven, Culture

However, before any change can occur there is one systematic fundamental that needs to be in place: an aligned culture based on shared corporate values and practices. Without a culture of consistency where all your people buy-in to the same vision and values and look to apply these in every action and interaction, disparate practices will exist and continue. Given the many different interpretations of Behavioural Economics, unless you have the cultural strength and learning structure to disseminate a defined approach, the way your people interpret Behavioural Economics will also be disparate.

For example, consider a hypothetical Wealth Management firm;

- They have grown rapidly through acquisition in the last five years

- They have a national presence with 12 regional offices

- They have 100 Regulated Individuals within the firm, 90% at Chartered Financial Planner Status

- 45% of employees have joined the firm in the last 3 years

At face value they are well established and operating comfortably in the post RDR fee based environment. However, the firm is riddled with different heritages, legacy processes and systems and they lack a consistent Value Proposition. Worse, many individuals feel no need to integrate more deeply with the firm’s central proposition, happy to continue as they are with their long standing clients. As a result, there is risk to both compliance and conduct which, as we have seen, impacts both the client experience and commercial outcomes. Yet the application of Behavioural Economics techniques here will not solve their problem. While advisers in our hypothetical wealth management firm would undoubtedly grasp the principles of Behavioural Economics, they would have difficulty applying these principles with any consistency as they are thinking and acting in silo. First a consistent culture must be created to enable the use of Behavioural Economics.

At Bigrock we are often asked what a great culture means… for us it’s when your values underpin employees’ behaviours, leading them in the right direction so they

“Know what to do, even when they don’t know what to do”

Every employee is driven by your organisation’s values, to the extent that they become part of the corporate social norming that subconsciously affects your people’s decisions, creating a climate where acting outside of these cultural precepts feels unnatural.

If you can develop a values driven culture of this strength, then implementing concepts like Behavioural Economics, where the ultimate decision or judgement lies with each individual, becomes much easier as the theories can be integrated into this cultural lexicon. In a company where every action is based on mutually shared values, a consistent approach to Behavioural Economics is much easier to embed, as every employee has a shared reference point to return to.

As such, our first challenge to you the reader is to ask whether your organisation has a strong enough culture to embed a set of theories as multifaceted, apparently contradictory and reliant on individuals’ ability to understand, recognise and interpret human interactions with consistency, as Behavioural Economics.

Many organisations, with the encouragement of the regulator, have been working on their culture over the last year, so some readers may feel confident in expressing an easy ‘Yes’. Yet, if you are unsure on the strength of your culture or doubt how far your values have infiltrated throughout your firm, we would strongly encourage you to consider enhancing your culture before or alongside any initiative to embed Behavioural Economics theories. We recommend beginning with a cultural assessment or evaluation.

Step 1 – Understand Behavioural Economics

The first step in improving your customer experience and commercial outcomes in light of what we’ve learned about people’s approach towards making decisions is to ensure every member of your organisation understands the theories of Behavioural Economics and how they apply in the context of our industry. As instructive as we hope this white paper is, this does not mean simply circulating this document to all employees. Firms serious about utilising Behavioural Economics to improve conduct and compliance must take a much more proactive approach. Education should begin at the top, with your leadership team to secure their support and ensure they understand how important these phenomena are when developing an effective framework for constructive conversations with clients and consumers. It should then be cascaded outwards to every employee. Care must be taken to ensure that the message is not filtered or simplified as it is cascaded throughout your hierarchies. All client facing employees must have a thorough understanding of the theories behind any new initiatives as one of the easiest ways to counteract heuristics is to explain to a client that they are unwittingly using them. For instance, a client is more likely to accept that they are wrong to hold on to a particular piece of information as the key benchmark, if the adviser can explain that the reason they feel this information carries more weight is because the brain is deploying the anchoring heuristics and is judging all previous information by this benchmark purely because it was one of the first ones seen. To do this all employees must feel comfortable with these concepts, particularly those at lower levels within your firm who may deal with clients on a more regular basis than those in senior leadership positions.

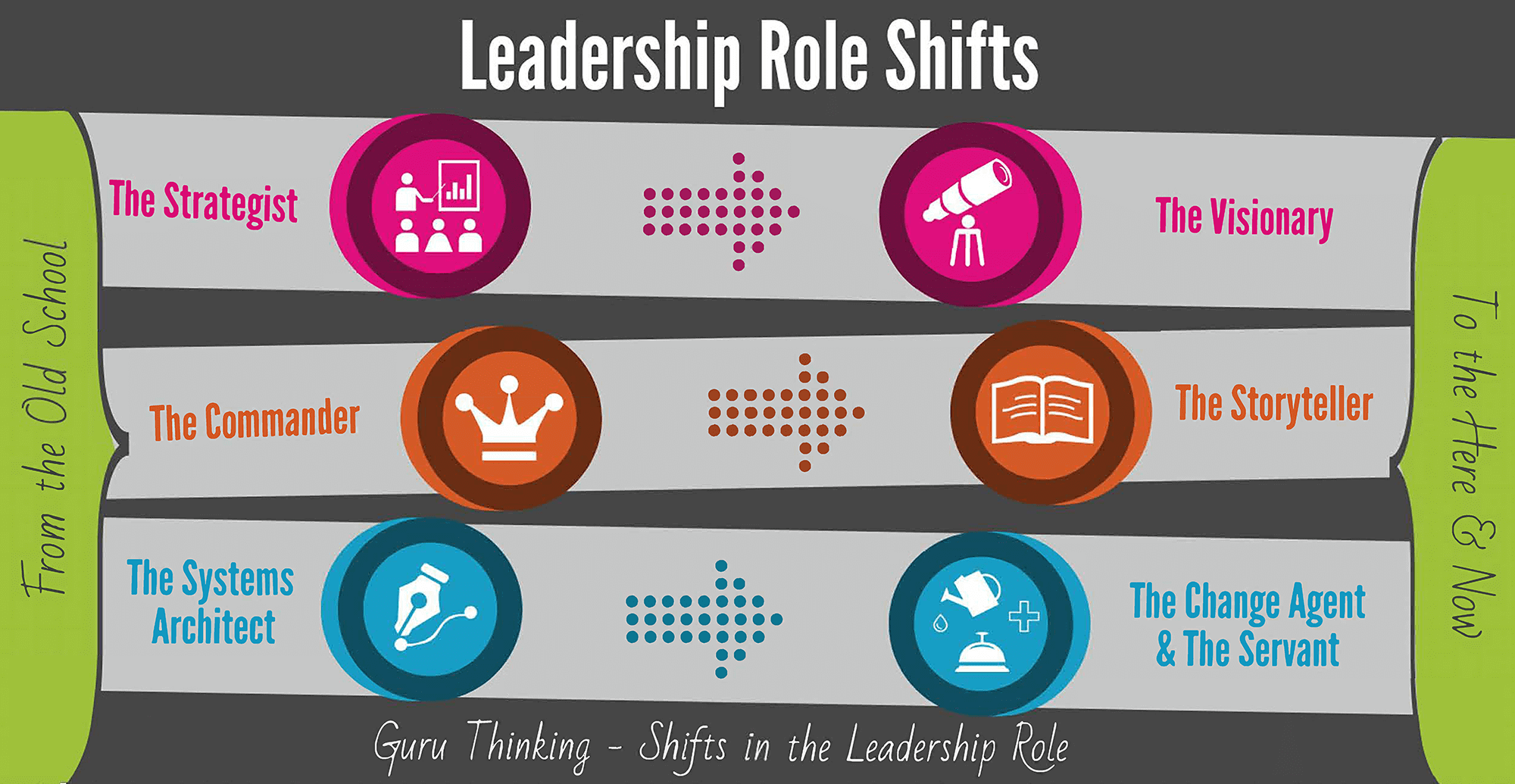

Here leaders should support their employees to support their clients. It is imperative that leaders recognise that to embed Behavioural Economics aligned processes they must take on the roles outlined in our recent infographic on Leadership Role Shifts, shown on the right (and available on our website). They must be the Visionary and Storyteller, promoting the importance of these phenomena and presenting it to employees; though most importantly they must be an Agent for Change and the Servant of their employees. Leaders must recognise that it is with the front line employees, whose conduct has the greatest and most direct effect on client experience, where an understanding of Behavioural Economics will have the most impact on their organisation and their clients.

The first step for the reader looking to apply Behavioural Economics within their firm is to gain commitment for a widespread Behavioural Economics learning programme, from the leadership team. Once this support is confirmed, gather a team to review your customer experience in light of Behavioural Economics and work out the art of the possible. We call this ‘Imagineering’ and it is an opportunity to discuss the merits of every idea and option open to you. All those who will be part of this Imagineering and Discovery team, who will decide what Behavioural Economic will mean to your organisation, must have a complete understanding of Behavioural Economics theories, the FCA’s commitment to Behavioural Economics and what these phenomena mean to the Financial Services industry and your sector in particular.

Educating all employees will be the first stage of any change programme. However, it is important that the theories are put in the context of your organisation’s customer journey. Therefore, in reality firms should complete steps 2-4 first. The Imagineering team must develop an understanding of what Behavioural Economics means for your clients and their experience, so that your new Behavioural Economics aligned approach can be clearly communicated to employees.

Step 2 – Understand your Customer Experience

Having selected an Imagineering and Discovery (ID) team and ensured they fully understand the principles of Behavioural Economics and its importance to a compliant and effective customer experience, the next step is for you to map your client / customer journey. Map out the possible journeys delighted, satisfied and unhappy customers take with you. Pinpoint areas where Behavioural Economics phenomena are likely to come into play, for instance:

- Where customers are given lots of new information

- Where customers are confronted with decisions or asked to make a choice

- Where customers are likely to have had similar previous experience

- Where they may be confronted with an entirely new experience

- Areas that may be highly emotive or stressful (e.g. closing an account after a bereavement)

- Areas that are particularly difficult for your advisers / sales people / distribution teams

Then discuss which heuristics are most likely to come into play at these points, whilst remembering that everyone’s use of heuristics and reactions are different. Could you adjust your processes to assist your customers or employees in any way that would improve the customer experience?

We also recommend you experience your customer journey for yourself. When did you last experience your own processes? Many organisations undertake mystery shopping exercises but often the outcomes of these (was the adviser helpful? Did he explain matters sufficiently?) are at a very basic level. Is a typical member of the public aware of what they should expect of an adviser? If Martin Wheatley (Chief Executive of the FCA) was your mystery shopper, would he draw the same conclusions? We strongly recommend leaders take an Undercover Boss approach, and attempt to experience what their customers do by surveying the frontline from the customer’s perspective. This will enable you to truly appreciate the customer experience, whilst critiquing your performance in a way the average mystery shopper, with their limited knowledge of regulation and best practice processes, cannot.

Step 3 – Decide how your ideal Customer Experience would incorporate Behavioural Economics

Now we would recommend you take a step back. Think about what an ideal Customer Experience would be. What do you want your clients to experience? What do you hope they feel about your organisation? How would you hope employees would treat a dissatisfied or frustrated customer? What does this mean for your processes and customer interactions? What is the best you can do that is a reasonable ask of your employees?

How in your ideal customer experience would advisers recognise and mitigate the effects of Behavioural Economics? Can you reduce or eliminate any behavioural economics hot points customer experience? How would your processes guide employees through the unavoidable Behavioural Economics hot points?

The answer to the questions, and the ideal that you will formulate as a result, will be different for every firm and will depend on your particular vision, values and culture, as well as the compliance required of your organisation and the particular field you are involved in.

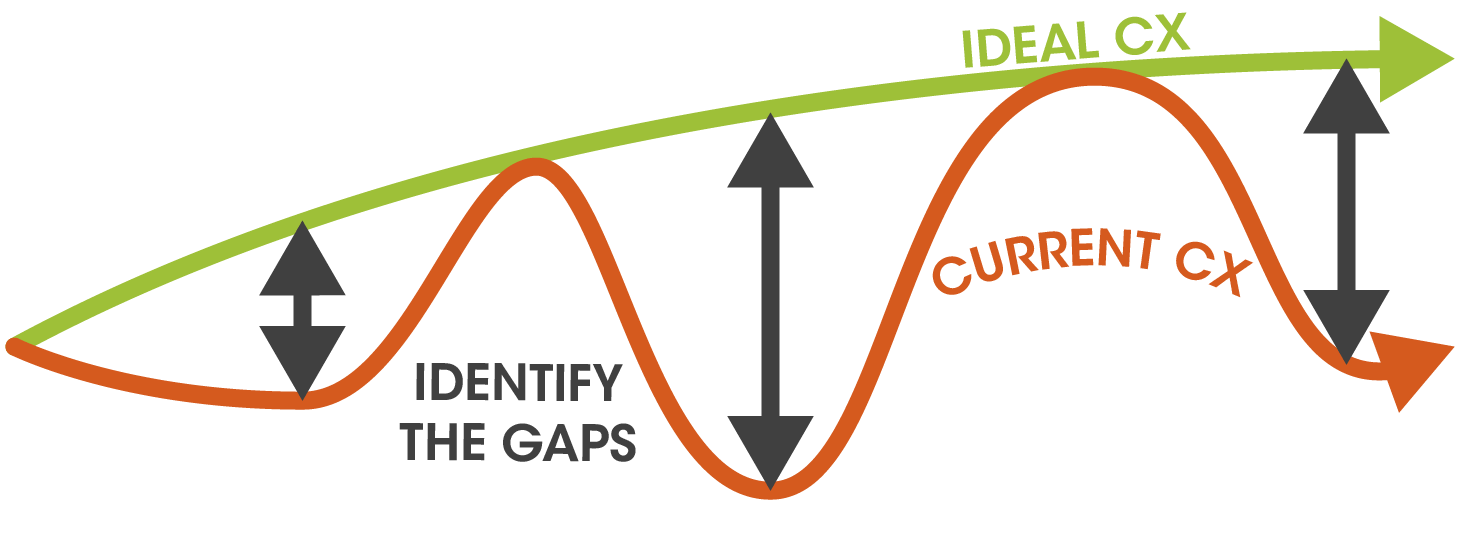

Step 4 – Identify the gaps between your current and your ideal Customer Experience

Once you have agreed a vision for your ideal customer experience, Step 4 involves a comparison. Compare the ideal you have imagineered with the reality you discovered and mapped out in Step 2. Where are the gaps?

Identify the areas where there is a discrepancy between your current customer experience and the ideal you have imagineered where your employees would utilise Behavioural Economics to guide customers towards the most appropriate product or service. This exercise enables you to focus on the exact areas you wish to improve. It will highlight both the areas where you wish to inject insights from Behavioural Economics and any areas where your customer experience can generally be improved.

Step 5 – Change!

Having identified your areas of need, the final step is to change. The exact change needed will obviously depend on the gaps identified.

Yet, any change programme should begin by inspiring and educating your employees about why you have decided to change. Explain the importance of Behavioural Economics to the customer experience, to compliance and conduct and thus to your commercial outcomes. Explain the process the ID team have undertaken to explore how Behavioural Economics can benefit your organisation and your clients. Emphasise that the objective is to help colleagues understand, communicate and build a relationship with their clients / customers that is both compliant and effective. Try to impress on employees that this is an iconic moment for the organisation, from which you will move into a new customer centric, Behavioural Economics aligned, era.